What are the practical differences?

When I start a new HERS rating or energy model the second conversation that typically comes up is the strategy for keeping the attic dry and mold free. Energy codes, building scientists and lots of bad experiences are collectively pushing us all towards sealed (AKA conditioned and unvented) attics. This means bringing the attic into the house, more like a very short second floor, so it is kept warm, and therefore dry, and therefore clean.

Please note that I am writing specifically about the region where we work- the mountains. Here it is a heating dominated climate; zones 5, 6 and 7. If we were talking about another climatic area the recommendations might be different.

What are the advantages of sealed attic construction?

•Whole house air leakage are typically significantly reduced which saves on heating and cooling energy, plus reduces ice damming

•Mechanical systems and ductwork located in a sealed attic operate more efficiently

•Controlled temperature and humidity increase structural integrity and decrease the possibility of condensation

•Increased temperature means decreased moisture which means decreased mold growth

•Rodents and insects are sealed out

•Increased home value or salability

Pros of building the sealed attic:

•no roof venting to install

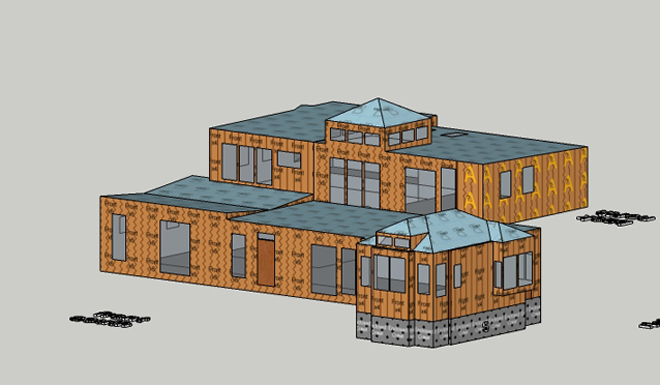

•complex roof are inherently difficult to vent, sealing may be the solution

•may increase the usable area of a house; this could actually penalize a house under LEED-H

•air sealing the ceiling is not necessary

•attic hatches do not need to be insulated and gasketed

•recessed lights do not need to be air-tight

•creates a conditioned space for storage*

Cons of building the sealed attic:

•Increases the volume of air in the house that gets heated; this could actually penalize a house in an energy model

•The depth of rafters may limit the overall depth of the insulation

•Material expense. It takes air-impermeable insulation to create a sealed attic; which is typically more expensive than air-permeable insulation.**

The bottom line is that both of these techniques are still totally legitimate, they both have pros and cons, you just need to choose the on that serves you best for the particular application.

One more thing: back-ventilated roofing. If you find yourself in a situation where ice dams or dangerous shedding from a pitched roof are critical, over an entry for instance, it may behoove you to keep the roofing as cold as possible. Snow itself is an insulator- roughly R1 per inch. So if there is snow on a roof, the isolative value will begin to capture the small amount of heat escaping through the roof. If it gets warm enough to liquefy the snow, then conditions exist for ice build-up and/or avalanche-like releases of snow and ice. The cure for this is to provide ventilation channels behind the roofing to keep it cold. This is why I don’t like to use the terms “cold roof” and “hot roof”, it just gets confusing. The corollary to this idea is that sometimes it makes sense to insulate an exterior porch roof. I have seen this at a ski lodge before- you have a large entry porch on the south side, as heat builds up under the porch, the roofing is quickly warmed and thousands of pounds of snow and ice launch off of the roof with a terrifying crash. Again the answer is keeping the roofing cold; insulate it and/or back-ventilate it.

*If the attic will be used for storage, then foam insulation has to have a 15 minute thermal barrier; which may require installing ½” gypsum board or plywood. If it is not used for storage, then it just requires an ignition barrier; typically 1 ½” of mineral fiber insulation.

**Air permeable and impermeable insulation can be mixed to create a successful hybrid assembly. The ratio of the two is stipulated in the IRC table 806.4 by climate zone.